Santa Gertrudis Asistencia

Santa Gertrudis Asistencia Monument, April 2018 | |

| Location | Approximately five miles north of Mission San Buenaventura on the Camino Real |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 34°20′51″N 119°17′49.5″W / 34.34750°N 119.297083°W |

| Patron | Gertrude the Great |

| Native tribe(s) Spanish name(s) | Chumash |

The Santa Gertrudis Asistencia, also known as the Santa Gertrudis Chapel, was an asistencia ("sub-mission") to the Mission San Buenaventura, part of the system of Spanish missions in Las Californias—Alta California. Built at an unknown date between 1792 and 1809, it was located approximately five miles from the main mission, inland and upstream along the Ventura River. The site was buried in 1968 by the construction of California State Route 33. Prior to the freeway's construction, archaeologists excavated and studied the site. A number of foundation stones were moved and used to create the Santa Gertrudis Asistencia Monument which was designated in 1970 as Ventura County Historic Landmark No. 11.

History

[edit]The Santa Gertrudis Asistencia was established as an asistencia or "sub-mission" of the Mission San Buenaventura, ministering to the Chumash people in the Ventura River valley where substantial agricultural activities were conducted.[1][2] The precise date of its creation is not known, though historians place its establishment during the time when the second church was being built at the main Mission, somewhere between 1792 and 1809.[1][3] The asistencia was named after Gertrude the Great, a 13th century German Benedictine, mystic, and theologian who was canonized in 1677.[4]

The asistencia was built along the route of El Camino Real, a historical trail that linked California's Spanish missions. The Camino Real turned north at the Mission San Buenaventura following the course of the Ventura River.[5] The Santa Gertrudis site was located 5.1 miles north of the mouth of the Ventura River and 220 feet from the river's east bank.[4] According to one account, it was situated near a sycamore tree used in rituals by the Chumash people. Sol N. Sheridan in 1926 described the site as follows:

The spot had always been a sacred one to the Indians. There at the point where the Casitas Pass road branches from the road to Ojai, stood their own sacred tree - a great sycamore under whose wide-spread boughs they had always assembled to worship their primeval god, and amongst whose leaves, even down to modern times, they used to hang their offerings of gay feathers and bright cloth and the skins of animals.[6]

During four periods of crisis at the Mission San Buenaventura, the Mission padres, according to some accounts, temporarily relocated to the Santa Gertrudis Asistencia.

The first possible relocation to Santa Gertrudis, and the one having the least historical support, followed a fire in the 1790s that destroyed the first Mission church. According to two accounts by Charles Hillinger published in the Los Angeles Times, "a temporary mission -- the little Mission Santa Gertrudis -- was erected and used for religious services until 1809 when the second church at Ventura was finally completed."[7][8]

The second relocation followed the 1812 San Juan Capistrano earthquake when the padres moved inland and remained for several months until the Mission was repaired.[1][3][7][9] During this time, adobe buildings and huts were built.[10] However, one Mission historian has argued that a February 1813 letter indicates that the 1812 relocation was not to Santa Gertrudis but to a site closer to the main Mission.[11]

The third relocation was in December 1818 due to the threat of invasion by Hippolyte Bouchard and his two ships of Peruvian pirates.[7][12] The padres relocated inland with the Mission's livestock and valuable items. Although the historical record is unclear as to whether Santa Gertrudis was the site of refuge, historian E. M. Sheridan wrote as follows in an unpublished account: "Miguel was put in charge of the advance guard of Indians to head northward and make arrangements for the reception at Casitas, at the Chapel of Santa Gertrudis which was considered far enough back as to become an abiding place until Bouchard and the expected pirates should have come and gone."[13]

The fourth relocation followed the 1857 Fort Tejon earthquake. Two historical accounts indicate that the 1857 relocation was to Santa Gertrudis.[1][14]

In the mid-1880s, the remains of the asistencia were plowed under when owner Salmon R. Weldon put the land under cultivation.[4]

Archaeological excavation

[edit]

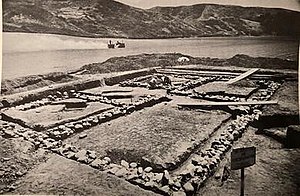

In the 1960s, the State of California planned to build California State Route 33 over the area believed to be the site of the Santa Gertrudis Asistencia. Prior construction of the freeway, the California Department of Highways entered into an inter-agency agreement with the California Department of Parks and Recreation to conduct an emergency archaeological salvage project.[15] Archaeologist Roberta S. Greenwood and R. O. Browne led the excavation with field work being conducted between March 8 and April 29, 1966.[15] Greenwood and Browne had previously conducted test excavations in November 1964 without success.[16]

During the 1966 excavation, the location of the asistencia was determined through the use of an 1853 map of Rancho Cañada Larga o Verde discovered at the Bancroft Library in Berkeley, California.[15][7][12] The excavation revealed the foundation of a structure measuring 15.5 meters by 11.25 meters, parallel to and facing the Camino Real. The foundation was built using large sandstone boulders believed to have been carried from the nearby Ventura River and placed in trenches. The structure had four rooms arranged in a U-shaped plan around a sheltered courtyard or patio.[17] Based on its size, its relation to the other rooms, and the presence of what appeared to be the main entrance, Greenwood and Browne concluded that Room 4, the largest in the structure, was used for worship.[18]

Although no remnants of walls were discovered, an adobe brick was found on the site, and Greenwood and Browne concluded that the walls were built with locally-fabricated adobe bricks.[19]

Greenwood and Browne found no intact roof tiles and hypothesized that Emigdio Ortega may have salvaged the tiles for the 1857 construction of the Ortega Adobe. Ortega had reportedly purchased roof tiles from the Mission padres after the 1857 earthquake. Comparison of 57 roof tile fragments from Santa Gertrudis with tiles at the Ortega Adobe showed them to be "identical in Munsell color, temper, and average size."[20] Greenwood and Browne further observed that the removal of the roof tiles was consistent with historical accounts of rapid and total disintegration of the adobe in the years that followed.[20]

Greenwood and Browne also hypothesized, based on an examination of floor-tile fragments from the chapel, that 35 tiles at the Rocky Mountain Drilling Company, located 275 meters northwest of the chapel, may have been salvaged from the chapel.[21]

Remains of two ovens or kilns located behind the structure were also discovered.[2]

Following the findings of the archaeological survey, many individuals and groups advocated for the relocation and restoration of the chapel, but no plan was adopted prior to the freeway's construction.[15][12] Accordingly, in January 1968, the remains of the chapel were removed from the path of the freeway and buried in a pit located 160 meters to the southeast of the building's original location.[15]

Santa Gertrudis Asistencia Monument

[edit]

In 1968, a number of the chapel's foundation stones were relocated to create the Santa Gertrudis Asistencia Monument. It is located approximately 500 feet south of the chapel's original location, on the east side of North Ventura Avenue three-tenths of a mile north of the Ventura Avenue Water Purification Plant (5895 N. Ventura Avenue). The monument was designated as Ventura County Historic Landmark No. 11 in December 1970.[22]

During the December 2017 Thomas Fire, trees adjacent to the monument were burned.[23] The monument itself, being made of stone, was unharmed.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Zephyrin Engelhardt (1930). San Buenaventura: The Mission by the Sea. Mission Santa Barbara. p. 26.

- ^ a b Roberta S. Greenwood; R. O. Browne (October 1968). "The Chapel of Santa Gertrudis". Pacific Coast Archaeological Society Quarterly. p. 41.

- ^ a b Greenwood and Browne, pp. 3 and 41.

- ^ a b c Greenwood and Browne, p. 7.

- ^ Greenwood and Browne, p. 6.

- ^ Sol M. Sheridan (1926). History of Ventura County, Volume I. S. J. Clarke. p. 51.

- ^ a b c d Charles Hillinger (May 2, 1966). "Two-Year Race Ends at Mission Dig: Archaeologists Beat the Freeway Bulldozers". Los Angeles Times. pp. II-1, II-2 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Charles Hillinger (July 13, 1964). "Freeway Building Spurs 'Lost' Mission Search: Archaeologists Dig in Ruins of Settlement Near Ventura for Santa Gertrudis Relics". Los Angeles Times. pp. II-1, II-3 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Old Mission Has Birthday". Ventura Free Press. April 7, 1911. p. 5.

- ^ C. M. Gidney; Benjamin Brooks; Edwin M. Sheridan (1917). History of Santa Barbara, San Luis Obispo and Ventura Counties. Lewis Publishing Co. p. 275.

- ^ Greenwood and Browne, p. 4.

- ^ a b c Jack O. Baldwin (November 20, 1966). "The Missing Mission and a Race With a Road". Independent Press-Telegram. pp. Sunday Magazine 4, 22 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Edwin M. Sheridan. untitled manuscript, Volume 2 of 7. unpublished. p. 39.(quoted by Greenwood and Browne, p. 4)

- ^ Mildred Hoover; Hero Eugene Rensch; Ethel Grace Rensch (1932). Historic Spots in California. Stanford University Press. p. 61.

- ^ a b c d e Greenwood and Browne, p. 2.

- ^ Greenwood and Browne, p. 9.

- ^ Greenwood and Browne, p. 13.

- ^ Greenwood and Browne, p. 15.

- ^ Greenwood and Browne, p. 17.

- ^ a b Greenwood and Browne, pp. 18 and 20.

- ^ Greenwood and Browne, pp. 20-21.

- ^ "Ventura County Historical Landmarks & Points of Interest" (PDF). Ventura County Cultural Heritage Board. May 2016.

- ^ Myers, Ched (January 10, 2018). "Remembering the Asistencia Santa Gertrudis". Archived from the original on 2018-05-05.